Formal analysis: metrical and musical structure

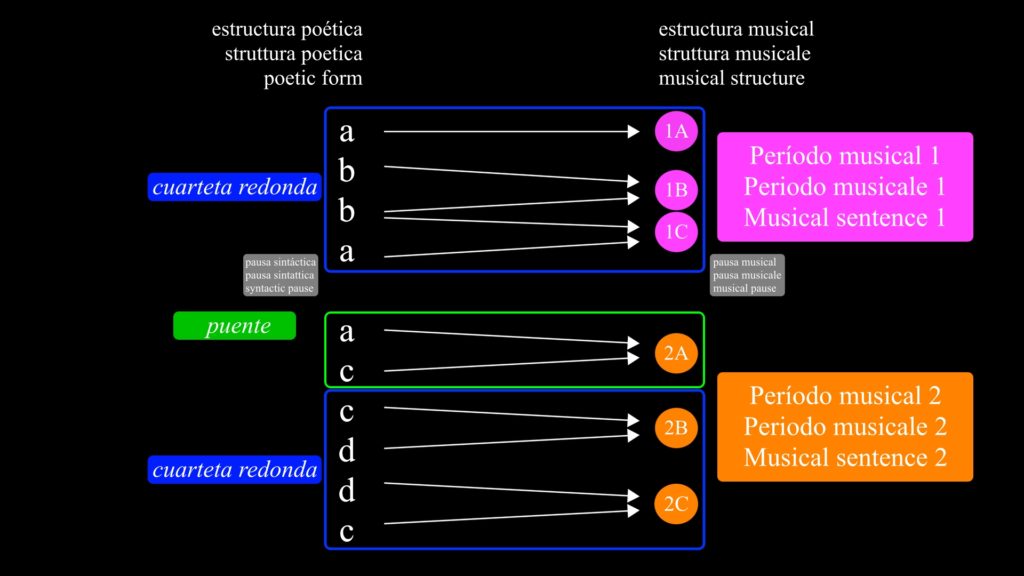

Fig. 4.1. Diagram of the relationship between metrical structure (décima espinela) and musical structure in a stanza of the verso Por Adán y Eva, as performed by Roberto Carreño in the video.

From a formal point of view, canto a lo poeta is based on specific poetic metrical forms (the cuarteta, the décima espinela and the verso), melodies (entonaciones) and instrumental accompaniments (toquíos).

The décima espinela

The main metrical form employed by the singers is the décima espinela, a stanza form created at the end of the 16th century and attributed to the Spanish poet and musician Vicente Espinel. Today, the espinela is one of the most widespread, lively poetic forms in the popular literatures of Latin America, particularly as regards oral tradition and improvisation. The espinela consists of ten octosyllabic lines (which the singers call vocablos) linked by rhymes according to the obligatory abbaaccddc scheme. In the canto a lo poeta tradition, unlike the canonical scheme, non-consonant rhymes are also allowed. Three sub-parts can be distinguished within the espinela: two envelope quatrains (lines 1-4, with abba rhyme, and 7-10, with cddc), called redondillas in Hispanic metrics and cuartetas cuadradas or cuartetas redondas in the Chilean context; and a puente (bridge) connecting them by their external rhymes (lines 5-6, with an ac rhyme).

Re – vien – tael – sol – en – la – pu – na a

a – rras – tran – do – su – ca – lor b

bro – ta – del – hie – loel – va – por b

queha – cia – los – cie – los – sea – cu – na. a

(¡Ay sí!)

Las – go – tas – u – na – por – u – na a

so – bre – ro – cas – es – car – pa – das c

lim – pias – des – cien – den – las – gra – das c

por – na – tu – ra – les – sen – de – ros d

for – man – do – rí – os – yes – te – ros d

Des – de – las – cum – bres – ne – va – das. c

(¡Ay sí!)

At the end of the first cuarteta or redondilla there is always a pause in syntax and meaning that separates the décima into two parts: the initial cuarteta (lines 1-4) sets out the theme or subject of the stanza, while the second part (lines 5-10) develops or expands on it. This pattern provides an extremely compact structure but at the same time is endowed with internal flexibility, which makes it especially suitable for extended narratives and improvisation.

The verso

Making use of the décima espinela, poets compose the verso, a poetic form based on the glosa procedure (i.e quoting lines from another poet). Each verso (a term that stands for a whole poem, not to be confused with verse as a single line of poetry) in its complete form is made up of a cuarteta (quatrain of eight-syllable lines) which is then “glossed”, i.e. developed or expanded in four décimas, each ending by returning to one of the four lines in the initial cuarteta. In the usage of Chilean cantores, the verso is sometimes completed by a fifth décima, with which the cantor takes leave of the audience.

An example of a verso: Décimas a lo humano por el agua

Décimas a lo humano por el agua (see the full Spanish text here) is an original composition by Erick Gil Cornejo. In the video on the first page of this guide, there is a clip of the first décima, interpreted by Erick Gil himself. The subject or fundado of the text – Por el agua – falls within the category of the canto a lo humano and in this case the poet uses it to address an issue by making an environmental and political critique, expressing his dissent over the privatisation of water resources, introduced by the neo-liberal policies of Chilean governments.

The entonación

The melodies to which the singers set their versos are called entonaciones. In general, each entonación can be associated with any verso or fundamento, at the singer’s discretion, and therefore becomes interchangeable with the texts. The instrumental accompaniment of the entonación is called the toquío (from the verb tocar, “to touch” or “to play”) and is usually performed on the guitarrón or guitar. The development of the entonación coincides in its overall duration with one décima, but its internal structure is articulated differently [Fig. 4.1.]: whereas the main syntactic pause divides the literary décima into two unequal parts (4+6 lines), the musical structure has two symmetrical periods of three phrases each (3+3). For the pause between the two musical periods to coincide with the pause in the text, the mismatch between the two structures must be compensated for. In the example analysed in the video Por Adán y Eva, we see how the compensation is achieved in the first cuarteta in two different ways: by lengthening the duration of the singing of the first line of verse until it coincides with a complete musical phrase and by repeating the third line.

The melodies have a certain variety, oscillating between the tonal arrangement and the memory of historic European modes. They generally move within a reduced range (the distance between the lowest and the highest note), between a minimum interval of a fifth and a maximum interval of an octave; they are mostly syllabic (each syllable corresponds to a single note) and psalmodic (the intervals between the notes are predominantly conjunct, by a tone or a semitone). The relationship between metrical and musical structure can also vary. In some melodies, such as the one sung here by Erick Gil, a short melodic and textural aside is introduced with the words “Ay sí”, added but not counted in the metric of the décima. A further element of rhythmic variation is provided by the diversity of accompaniments (toquíos) associated with the entonaciones. On the other hand, a fixed element is the presence of descending melodic curves (caídas) at the fourth and tenth lines of the décima, i.e. the conclusion of each of the two musical periods making up the entonación.

The video shows the metric and musical structures of the first décima of Por Adán y Eva, sung by Roberto Carreño. In his interpretation, the phrasing of the song tends to be stretched to avoid coinciding with the more regular accentuation of the toquío.